Global Action Agenda

The Global Action Agenda

A vision for implementing and translating climate and mental health research

Contributors to this agenda emphasised that how research is done matters, at least as much as what research is done. This action agenda outlines how climate and mental health research can be better implemented, and how to link this research with action to ensure evidence is translated into policy and practice. It sets out:

- A vision for climate and mental health research, grounded in the reflections of the CCM community and structured into five components (Table 5, Figure 6).

- Challenges currently holding back progress to achieving this vision (Table 5).

- Example actions that key actors can take to achieve this vision.

‘Key actors’ is used to refer to: researchers and research funders across disciplines, policymakers and practitioners across sectors, educators and civil society (encompassing communities, community-based organisations, non-governmental organisations etc).

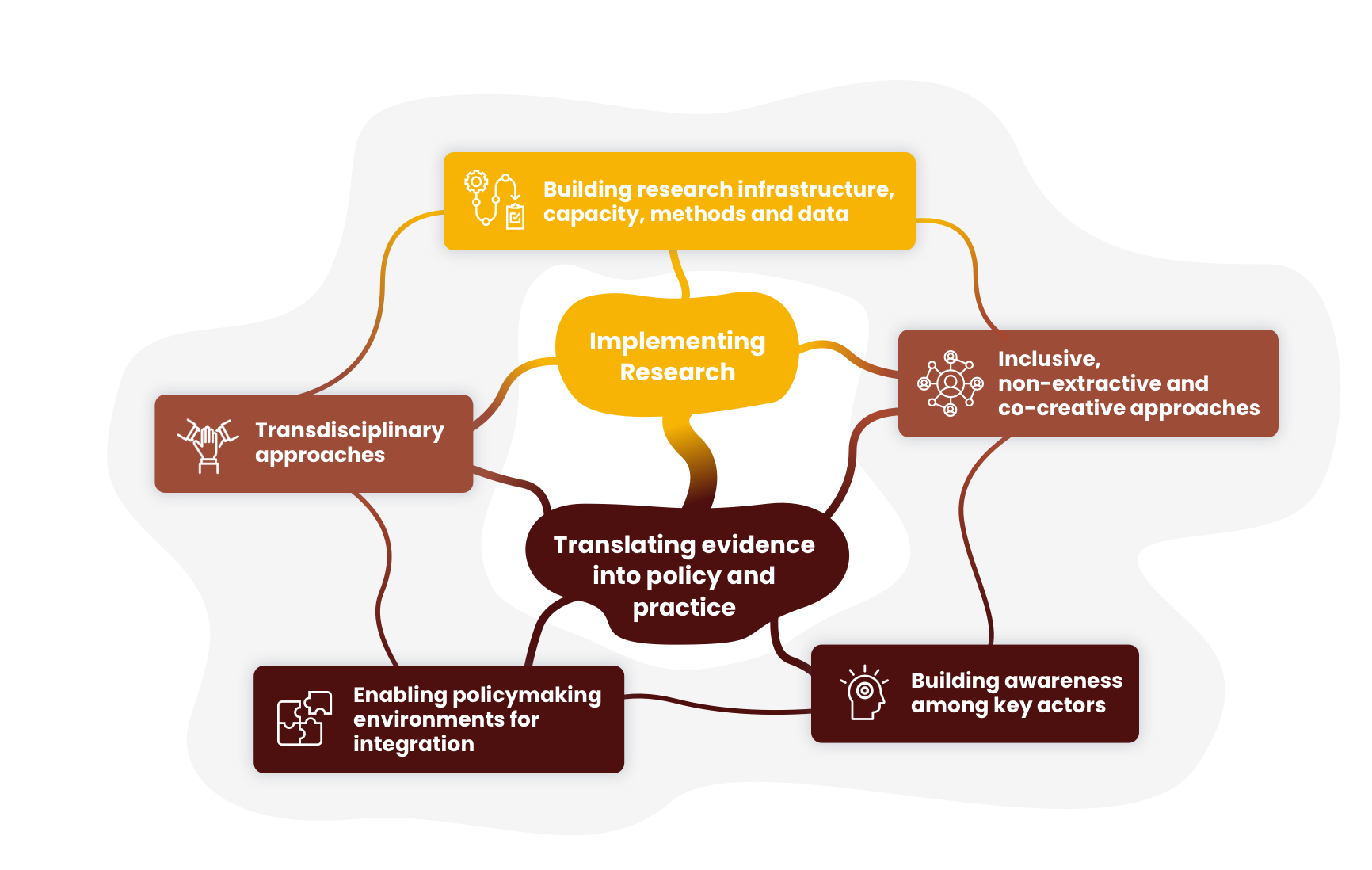

Figure 6: Key components of the vision for climate and mental health research. These components are interacting (e.g. one action may contribute towards multiple components of the vision), and aim to improve implementation and translation of research.

Figure 6: Key components of the vision for climate and mental health research. These components are interacting (e.g. one action may contribute towards multiple components of the vision), and aim to improve implementation and translation of research.

| Table 5: Five key components of the vision for climate and mental health research, and challenges holding back progress | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vision | Challenges holding back progress towards this vision | Hearing from the CCM community |

| Research infrastructure, capacity, methods and data: Consistent climate change and mental health methods and metrics exist, enabled by robust, available and appropriate data, with shared understandings of key climate change and mental health concepts. These are developed and applied with consideration of diverse wisdoms across disciplines, cultures, contexts and communities, reflecting both the need for comparison across contexts and the importance of adaptation to local understandings. Researchers across disciplines are supported to build systems thinking skills and engage in climate and mental health research as a primary focus or as an important component of work in their relevant discipline, and to do so in ways that support their own wellbeing. Such approaches enable inclusive, accessible, culturally sensitive, and policy-relevant research to be prioritised and implemented. | Lack of consistent and standardised methods, metrics and terminology for climate change and mental health. There is a tension between the need for standardisation for comparison, and for adaptation to local contexts that reflect cultural and linguistic diversity in how climate change-related mental health challenges are conceptualised, understood and experienced. Good quality and consistent data is often unavailable and inaccessible, particularly for mental health population and surveillance data. Lack of data sharing: Weak and fragmented health and research information systems can impact data management, knowledge sharing and collaboration, and big gaps remain particularly for global mental health data. Security issues regarding public sharing of national and global data on climate change and mental health may also lead to lack of trust among potential participants. Lack of research and institutional capacities in climate change and mental health across relevant knowledge and skills, personnel and funding, including to enable people from diverse backgrounds to come into the space. Lack of capacity may be worsened by burnout as a response to psychologically difficult work in climate, mental health and related fields without appropriate support. Politicisation of climate and mental health issues may also hold back researchers from getting involved or being able to secure funding. | "We need to learn from the community how they express their understanding of what’s going on. It may not be the same as us, as researchers." (Central and Southern Asia Dialogue participant) “By recognising and valuing these interconnected dimensions held by some Indigenous communities for what Western paradigms call mental health and/or mental wellbeing, we can move beyond the limitations of such dominant frameworks, fostering culturally responsive approaches that aligns with the rich tapestry of Indigenous wisdom and knowledge.” (Indigenous Research and Action Agenda) |

| Transdisciplinary approaches that combine and equally value multiple forms of expertise across disciplines, sectors, communities and contexts. Deep, sustained relationships are built at 'the speed of trust' (ie. with appropriate investment of time and continuous relationship building that is responsive to needs). These relationships and approaches enable diverse narratives and understandings to coexist and learn from each other. Embedded systems thinking enables climate and mental health to learn from and connect what is already known (e.g. in other research fields, other responses to societal challenges that require urgent and collective responses, and community-based knowledge and practices). Such approaches underpin how knowledge is generated, shared and translated into action. | Disconnections between key actors and silos within these groups. Research funding structures that may inhibit participation from multiple disciplines, cultures and/or countries being valued equally. Investment in sustainable field building for climate and mental health is critically needed, but is held back by challenges in funding research networks and in quantifying their follow-on impact. Research funding timescales with short term funding and/or one-off funding limiting the building of trust and sustained relationships forming and surviving. Restrictive scopes and limited resources that hold back dissemination of transdisciplinary research, such as the siloed scope of many academic journals, and limited funding, career incentives or allowances, time, and channels for knowledge sharing. | “We need collaborative research that is transdisciplinary, cross-sectoral, international and multigenerational; it must be anchored in equity, justice and a deep commitment to applying research findings and lessons learned to inform policies and practices.” (Eastern and South-Eastern Asia Research and Action Agenda) “Systems for academic advancement are not well aligned with transdisciplinary research or translational science, further preventing collaboration. These reward systems need to be overhauled to encourage transdisciplinary and inclusive climate-mental health research.” (Europe and Northern America Research and Action Agenda) |

| Inclusive, non-extractive and co-creative approaches: Research elevates, empowers and centres community and lived experience leadership, supported by research and funding structures that enable - and mandate - these approaches. Research considers and practically implements ways to avoid perpetuating the harms caused by the extractive, colonial, and unjust roots of both the causes and consequences of climate change (which currently perpetuate existing inequities and vulnerabilities and compound mental health impacts of climate change). Research ensures clear and tangible benefits for involved communities. | Extractive research practices 1) at the community level (e.g. lack of research impact or benefit for communities, lack of ownership and data sovereignty for involved communities) leads to participant fatigue, distrust in research, and limited pathways to impact; 2) by Global North researchers and institutions towards Global South researchers and participants, rooted in historical and current injustices. Exclusion of lived experience voices, groups most affected by climate change, and of Global South expertise in research and the development of policies and interventions. Inequity and inaccessibility of funding, with processes that often favour Global North researchers and institutions, including in definitions of climate change and mental health concepts and terminology. Compounding challenges in areas with limited access to advanced technology, electricity and internet outages, infrastructure, competing pressures and priorities, and mental health stigma. | “To decolonise and reindigenise research means to value Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing as equal to Western ontologies and epistemologies.” (Oceania Research and Action Agenda) “Youth should also be involved at decision-making levels designing agendas and research. They should be in the room to make their voices heard. Yet, this also needs to come from adults and decision makers realising they need to provide this space for young people to even participate.” (Youth dialogue participant) |

| Political and policymaking environments that enable integrated climate and mental health policies, practices and frameworks: Researchers are equipped with the skills to advise and learn from policymakers, inform evidence-based climate and health public narratives, and leverage growing momentum in the climate and health space to ensure that mental health is embedded in discourse and action. Policymakers from relevant sectors are able to connect across existing siloes to integrate mental health into relevant climate and health policies, practices and frameworks (and vice versa). | Siloed decision making, governance mechanisms and budgets between sectors and government structures (e.g. across climate change and mental health) holding back research, multi-sectoral collaboration and integrated policies. Lack of political will or prioritisation of climate change, mental health and the intersection. This may be exacerbated by competing priorities, crises, conflicting interests, or politicisation of climate change, as well as mental health stigma in some contexts. Reactive policy making around climate change and mental health (rather than being proactive and strategic), with urgency of the issues outpacing research and action. Under resourced systems with little capacity to integrate additional considerations (e.g. health systems). | “Realising demonstrable progress requires dedicated leadership, resources and political will alongside sustained, inclusive participation from all sectors of society.” (Northern Africa and Western Asia Research and Action Agenda) “Mental health is an under-prioritised issue for many governments. This relates to an overall lack of political will for action on climate-mental health, perhaps due to stigma, political risk and/or pressure, or the siloed nature of government preventing ministries from taking action.” (Europe and Northern America Research and Action Agenda) |

| Awareness among key actors of climate change and mental health impacts and what actions they can take to better understand and respond to these impacts: Key actors are aware of the multiple aspects and impacts of the climate change and mental health intersection, and are equipped with the knowledge, tools and capacity to respond effectively, appropriately and collaboratively. Climate change and mental health communication and awareness raising (e.g. terminology) is culturally contextualised, aligns with community understandings, and actively works towards de-stigmatisation of mental health in the context of climate change. | Lack of awareness, understanding and education on the intersection of climate change and mental health across key actors, including the different ways these issues manifest across cultures and communities. This includes inappropriate or misapplied awareness-raising that may lead to pathologising of healthy experiences (such as being concerned about climate change) or to more distress about being distressed45. Attitudes and beliefs around mental health and climate change (e.g. stigma, scepticism and denialism), and social, cultural and religious norms that may not align with interest in the issues or enabling research and implementing climate change and mental health solutions. Lack of clarity in the climate change and mental health field and/or mental health practitioners concerning the distinction and relationship between the wellbeing space (e.g. emotional responses to climate change) and clinical mental health considerations. Disproportionate media attention that certain constructs (e.g., climate anxiety) receive, can make it challenging to convey the multiple aspects of the interconnections between climate change and mental health to the public, policymakers, funders, and philanthropists. | “Addressing the topic of mental health is something very serious. You can't keep saying it anywhere, anytime, anytime. And even associating it with the issue of climate change is even more complex….People are always saying, ‘We need to talk about it.’ Until recently, we couldn't even talk about suicide, for example. We couldn't even talk about depression.” (Latin America and the Caribbean Dialogue Participant) |

Recommendations for action

Key actors all have a role to play to implement this agenda. Example practical actions are outlined below. Some of these may be unique to the climate and mental health field. Others are applicable across research fields, but included as they emerged through CCM as foundational for field building in climate and mental health.

Researchers should:

- Prioritise inclusion of communities and groups most affected by climate change and its mental health consequences in research teams and projects, to improve alignment between research aims, outcomes and benefits to communities. Build these relationships over time and be led by the needs of these communities. Support civil society to translate research findings into action, for example by ensuring relevance and accessibility of research to communities.

- Convene experts to establish conceptual frameworks for climate and mental health, and consistent indicators, metrics and methods to measure the mental health impacts of climate change and of climate action, that are appropriate for different local contexts, and that can be disaggregated across relevant population groups.

- Build, maintain and seek funding for relevant networks (and platforms) to share best practice, elevate existing knowledge (e.g. held in communities) and improve shared understandings across disciplines of relevant climate and mental health concepts, terminology, methods and dissemination, that allow multiple forms of knowledge and narratives to exist in parallel.

- Leverage existing areas of research interest, data and capacity where mental health impacts of climate change could be integrated (e.g. growing interest in climate change and (physical) health; impacts of heat exposure, food security) and build relationships with decision makers, to elevate awareness of the full scope and importance of the climate and mental health field and ensure equal status between physical and mental health in climate and health work.

- Establish (in partnership with communities) open data security, privacy and sharing protocols which encourage data sharing and increase trust in research for potential participants, translated into multiple languages. Link with existing principles and protocols for data collection, management and sharing, such as data sovereignty46,47 and the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) guiding principles48.

Research funders should:

- Collaborate with other funders from different disciplines, such as health and environmental funders (e.g. establishing or joining cross-issue networks, leveraging existing funding structures that do prioritise transdisciplinary climate and mental health research).

- Fund platforms where relevant aggregated data for both climate change and mental health (and on subgroups), research methodologies, literatures, initiatives, potential emerging interventions, and organisations are placed and updated annually and can be tailored to specific contexts.

- Fund capacity and field building initiatives. This includes the development and maintenance of transdisciplinary climate and mental health research networks to enable collaboration and shared learning (e.g. across Global South and Global North), establishing conceptual frameworks and consistent climate and mental health metrics, capacity building in countries with less climate and mental health research to date, and in establishing the follow-on impact of such connective and capacity-building activities.

- Increase access to and inclusivity of funding across geographies and types of expertise relevant to climate and mental health, including access to in-country and direct civil society funding to allow true ownership of the research.

- Mandate inclusion of communities and community-based organisations in climate and mental health research funding applications, with clear and tangible benefits back to the communities involved based on their stated desires and needs.

Policymakers and practitioners should:

- Integrate mental health and psychosocial considerations into relevant climate and health policies, practices and frameworks (and vice versa). This includes, but is not limited to, National Adaptation Plans and Nationally Determined Contributions, disaster risk reduction and preparedness activities, climate-informed mental health surveillance systems, climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessments, heat action plans, inclusion of climate considerations in mental health system planning. Identify and learn from evidence-based case studies where this is already happening, and highlight these as examples of what works (e.g. see CCM case studies).

- Connect across decision-making silos to explore how climate and mental health funding and strategic decisions across sectors can take into account relevant costs, trade offs and benefits of climate action for mental health (e.g. ensuring appropriate support for people moving out of the fossil fuel industry to other careers, accounting for the mental health benefits of reduced fossil fuel use through improvements to air pollution and reduction in climate risks).

Educators should:

- Incorporate climate change and mental health into relevant educational curricula (in schools, universities and continuing professional development) across various disciplines to encourage systems thinking and collaboration (e.g. medicine, public health, climate and environmental science, policy, psychology), to build capacity to recognise and respond to the mental health impacts of climate change. These programs should be robustly evaluated in terms of their impact and appropriateness.

Civil society should:

- Empower the co-creation of climate and mental health research and practice by exploring ways to connect with other community-led organisations or NGOs working on climate change and/or mental health, and through platforms such as the CCM Global Online Hub Collaboration Area and the Regional Communities of Practice. Share knowledge on best practice and current solutions being implemented by civil society with others through participation in such networks/platforms.

- Work with researchers to incorporate relevant evidence and research outputs into advocacy efforts and relevant work on the ground. This includes incorporating mental health considerations into climate and health or climate mitigation and adaptation activities being led by civil society (and vice versa).

- Lead on effective climate and mental health monitoring and communication mechanisms to gather information on quickly moving challenges on the ground and have that data feed into research priorities and policy and practice processes.

Resources developed through CCM can help guide and inspire those seeking to enact this agenda and include:

- Case studies showcasing existing climate and mental health research, interventions and policies

- Lived experience stories from around the world

- Toolkits for researchers, humanitarian decision makers and on lived experience engagement.

- Foulkes L, Andrews JL. Are mental health awareness efforts contributing to the rise in reported mental health problems? A call to test the prevalence inflation hypothesis. New Ideas Psychol. 2023;69:101010.

- Kukutai T, Taylor J. Data sovereignty for indigenous peoples: current practice and future needs. In: Kukutai T, Taylor J, editors. Indigenous Data Sovereignty. ANU Press; 2016. doi:10.22459/CAEPR38.11.2016.01.

- Smith D. Governing data and data for governance: the everyday practice of Indigenous sovereignty. In: Kukutai T, Taylor J, editors. Indigenous Data Sovereignty. ANU Press; 2016. doi:10.22459/CAEPR38.11.2016.07.

- Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 2016;3:160018.